As developers we often need to implement complex workflows. Test-driven development is a good way to develop that business logic in a safe way, but often I find its process a bit too dogmatic. My way of coding is sometimes more exploratory and it feels tedious to write all the unit tests before, run them, see them fail, code, rinse and repeat… In this post I present my take on writing complex business logic code with 100% unit test coverage, which I call Test Supported Development.

Requirements

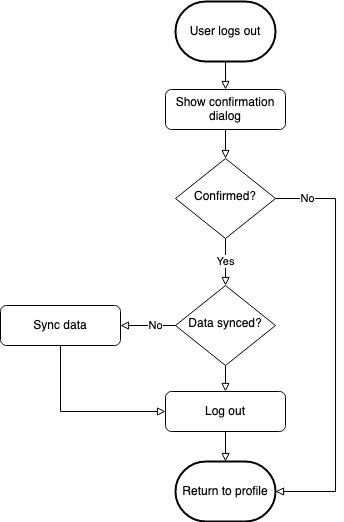

Let’s say we need to implement a logout flow which could look something like this:

Or put into words:

- When the user taps the “Log out” button, show a confirmation dialog to ask if they really want to log out.

- If the user does not confirm, return to the profile screen.

- If the user confirms, check if the user data is synced to the backend.

- If the data is synced, actually log out the user. Otherwise first sync the data and then perform the logout.

- Finally, return to the profile screen.

What at first seems to be the simple task of logging out a user quickly becomes a complex piece of logic involving the UI and the backend. “Traditionally” one might be tempted to implement this in the profile view controller. This is exactly what causes Massive View Controllers which are impossible to test.

Logout Use Case Class

Instead, I like to completely separate the business logic from any dependency on UI or other parts of the codebase. Usually I do this by implementing a use case class and thinking about how the public interface for this use case should look like. A use case class does only one specific thing and has as few implicit dependencies as possible (ideally none).

Public Interface

I usually start by looking at the problem from a caller’s point of view. How would I like to use this new API? We want to implement a use case that logs out the user. This will involve a backend request to delete the access token, so it is probably going to be asynchronous. So let’s start with this:

class LogoutUseCase {

func logout(completion: @escaping (Bool, Error?) -> Void) {

}

}Protocols, Dependency Inversion and Dependency Injection

Next we will need something that shows a confirmation dialog and returns whether or not we should actually log out the user. But at this stage we don’t care about the concrete implementation of the dialog yet, so that something will just be an abstraction.

This is where the SOLID design principles come into play, specifically the Dependency Inversion principle. Instead of depending on the actual confirmation dialog implementation we will just depend on its abstraction. In Swift we do this with protocols.

protocol LogoutConfirmationPresenting {

func showConfirmationDialog(completion: (Bool) -> Void)

}Now we still need a way to talk to that abstraction. We do this by injecting it as a dependency into the use case class:

class LogoutUseCase {

private let logoutConfirmationPresenter: LogoutConfirmationPresenting

init(logoutConfirmationPresenter: LogoutConfirmationPresenting) {

self.logoutConfirmationPresenter = logoutConfirmationPresenter

}

// The completion handler has a Bool indicating the success of the logout flow.

// The Error will provide more context in case logout failed.

func logout(completion: @escaping (Bool, Error?) -> Void) {

logoutConfirmationPresenter.showConfirmationDialog { shouldLogOut in

}

}

}Tests

So far we didn’t write any tests because there was nothing to test yet. But with the last code block we actually have the first piece of testable logic:

Before logging out, show a confirmation dialog.

Let’s write a unit test to check that behavior.

class LogoutUseCaseTests: XCTestCase {

// 1

var sut: LogoutUseCase!

var mockLogoutConfirmationPresenter: MockLogoutConfirmationPresenter!

override func setUp() {

// 2

mockLogoutConfirmationPresenter = MockLogoutConfirmationPresenter()

sut = LogoutUseCase(logoutConfirmationPresenter: mockLogoutConfirmationPresenter)

}

// 3

func test_logout_showsConfirmationDialog() {

sut.logout { _, _ }

XCTAssertTrue(mockLogoutConfirmationPresenter.didShowConfirmationDialog)

}

}

// 4

class MockLogoutConfirmationPresenter: LogoutConfirmationPresenting {

var didShowConfirmationDialog = false

func showConfirmationDialog(completion: (Bool) -> Void) {

didShowConfirmationDialog = true

completion(true)

}

}There are several things happening here. Let’s break it down:

-

The

sut(system under test) is theLogoutUseCaseclass. Because it depends on an object implementing theLogoutConfirmationPresentingprotocol, we need to create a mock implementation of that (4). -

The

setUp()function is called before each unit test. We create fresh instances of all the mocks and thesuthere, injecting the mocks through the initializer. -

This is the actual unit test checking if, when

logout(completion:)is called, at some point also the confirmation dialog is shown. -

The mock implementation implements the required protocol functions. Instead of executing any logic, it just sets the

didShowConfirmationDialogproperty totrue, which can then be asserted in the unit test and is proof that the function was indeed called.

Let’s look back at our flowchart. We successfully tested that the confirmation dialog is shown.

Now we need to handle its result.

User Cancels Logout

The completion handler in logout(completion:) has a Bool and an Error? parameter. Let’s say that when a user cancels, the logout was not successful und we want to let the user of the function know what happened.

class LogoutUseCase {

// 1

enum LogoutError: Error {

case userCancelled

}

...

// 2

func logout(completion: @escaping (Bool, LogoutError?) -> Void) {

logoutConfirmationPresenter.showConfirmationDialog { shouldLogOut in

// 3

if !shouldLogOut {

completion(false, .userCancelled)

return

}

}

}

}- We introduce a new Error enum which will contain all the reasons why the logout could fail. One of them is the user cancelling in the confirmation dialog.

- Instead of the generic

Errortype we now return our concreteLogoutError. showConfirmationDialog()’s completion handler returns aBoolindicating whether the user confirmed or not. If they declined we calllogout()’s completion handler withfalseand the appropriate error case.

Again one more testable piece of logic!

class LogoutUseCaseTests: XCTestCase {

...

func test_logout_userCancelled_returnsUserCancelledError() {

// 1

mockLogoutConfirmationPresenter.stubShouldLogOut = false

sut.logout { _, error in

// 2

XCTAssertEqual(.userCancelled, error)

}

}

}

class MockLogoutConfirmationPresenter: LogoutConfirmationPresenting {

var didShowConfirmationDialog = false

var stubShouldLogOut = true

func showConfirmationDialog(completion: (Bool) -> Void) {

didShowConfirmationDialog = true

// 3

completion(stubShouldLogOut)

}

}-

We add a new test that checks if the correct error case is returned when the user cancels the confirmation dialog. Now we need to control how the logout should behave in order to check the result. Therefore the mock got a new stub variable, defining the returned value of

showConfirmationDialog(). In this case we want to simulate the user pressing the “Cancel” button, sostubShouldLogOut = false. -

In the completion handler we assert if indeed the expected error was returned.

-

Instead of always returning

true, the mock now returns whatever has been assigned tostubShouldLogOut.

One more down. Back to the flowchart:

User Confirms: Check if Data is synced

If the user confirms the logout we want to make sure that all data is synced to the backend before removing it from the device. But again, at this stage we are not interested in how that actually works. We just want to have something we can ask if the data is synced. Time for another protocol!

protocol SyncStatusChecking {

func checkIfDataIsSynced(completion: (Bool) -> Void)

}In the same way as before we now add this as a dependency to our use case class:

class LogoutUseCase {

...

private let syncStatusChecker: SyncStatusChecking

init(logoutConfirmationPresenter: LogoutConfirmationPresenting,

syncStatusChecker: SyncStatusChecking) {

self.logoutConfirmationPresenter = logoutConfirmationPresenter

self.syncStatusChecker = syncStatusChecker

}

}Let’s use it in the logout() function.

func logout(completion: @escaping (Bool, LogoutError?) -> Void) {

logoutConfirmationPresenter.showConfirmationDialog { shouldLogOut in

if !shouldLogOut {

completion(false, .userCancelled)

return

}

self.syncStatusChecker.checkIfDataIsSynced { inSync in

}

}

}And again, as before, we have a new piece of logic that can be unit tested. Now we can add a test checking if syncStatusChecker.checkIfDataIsSynced() is called at some point. Please refer to the GitHub project for the implementation.

Rinse and Repeat

Repeat this process until the whole workflow logic is in place and covered by unit tests. The final version of the initializer with all dependencies looks like this:

init(logoutConfirmationPresenter: LogoutConfirmationPresenting,

syncStatusChecker: SyncStatusChecking,

dataSyncer: DataSyncing,

logoutHandler: LogoutHandling) {

self.logoutConfirmationPresenter = logoutConfirmationPresenter

self.syncStatusChecker = syncStatusChecker

self.dataSyncer = dataSyncer

self.logoutHandler = logoutHandler

}Each of the dependencies is mocked in the unit tests and all possible paths in the workflow are covered.

A caller of the use case would then write something like this:

let dataSyncer = BackendDataSyncer.shared // implements SyncStatusChecking and DataSyncing protocols

let apiClient = APIClient.shared // implements LogoutHandling protocol

let useCase = LogoutUseCase(logoutConfirmationPresenter: self, // e.g. in a view controller

syncStatusChecker: dataSyncer,

dataSyncer: dataSyncer,

logoutHandler: apiClient)

useCase.logout { success, error in

...

}Check out the project on GitHub with the full implementation of the workflow and tests.

Conclusion

Breaking down and implementing a complex workflow piece by piece makes it much easier to tackle. Tests evolve at the same time as the implementation. Because there are no intrinsic dependencies this approach makes it easy to refactor and fast to iterate on. If done consistently you will end up with 100% test coverage of your business logic.

Let me know what you think. You can contact me either via Twitter or email.